There's no shortage of food writers who cover restaurants, focusing on recipes and ingredients, across Canada; but there's only an invested few that really aim to dig into our past to find out what Canadian food is all about. Amy Jo Ehman is one of those individuals.

As a born-and-raised Saskatchewan farm girl, a freelance writer and columnist with StarPhoenix, Ehman enthusiastically dives into heritage recipes, sharing her findings with eager readers. Naturally, Ehman would be a perfect resource when it came to looking back at how the two major world wars affected the food Canadians consumed.

When her second book, Out Of Old Saskatchewan Kitchens, came out earlier this year, it was more than clear that Ehman knows the ins and outs of this prairie area, its immigrant settlers who started out with next to nothing, their growth into stable colonies that would later transform into farming communities, towns and cities that somehow through those really, really damn cold winters, found a way to feed themselves and make those Saskatchewan ingredients taste pretty damn good.

Though the cookbook focuses on the province between mid-19th century to early-20th century, she wound up discovering a lot about the effects of World War on the sprouting food culture in Saskatchewan way back when.

Here are five bits of Canadian food history that Ehman was more than happy to share with Eat North, so consider this a little bonus from a lovely cookbook that tells a tale (along with 80 recipes and some great vintage images that include harvest cakes and jam tarts) about part of our country's background that many of us really know nothing about.

A home cook's go-to ingredients were sent overseas to the troops.

Demand for meat, sugar, butter and fat (butter and lard) for the war effort caused shortages here at home. These foods were sent overseas to feed allied troops and the British populace. Here at home, family cooks were encouraged to use alternates such as fish, beans, molasses, syrup, brown sugar and vegetable shortening (such as Crisco). Canning and gardening were encouraged, as was cooking with seasonal local foods.

Kitchen by-products head to the battlefields.

Glycerine was extracted from fat and then used to make explosives in war ordinance. Home cooks were encouraged to pour kitchen grease into a can and take it to the butcher, who collected it for the war industry. A wartime slogan read: "One tablespoon of kitchen grease fires five bullets."

Margarine > butter. Well, temporarily, anyway.

Interestingly enough, margarine was banned in Canada until 1948, thanks to a strong dairy lobby. However, it was allowed from 1917 to 1923 due to the shortage of butter post-WWI. In 1948, the ban was repealed by the Supreme Court of Canada. Incidentally, this was imperative for the entrance of Newfoundland into Canada in 1949 because it had a significant margarine industry.

Canadian culinary propaganda.

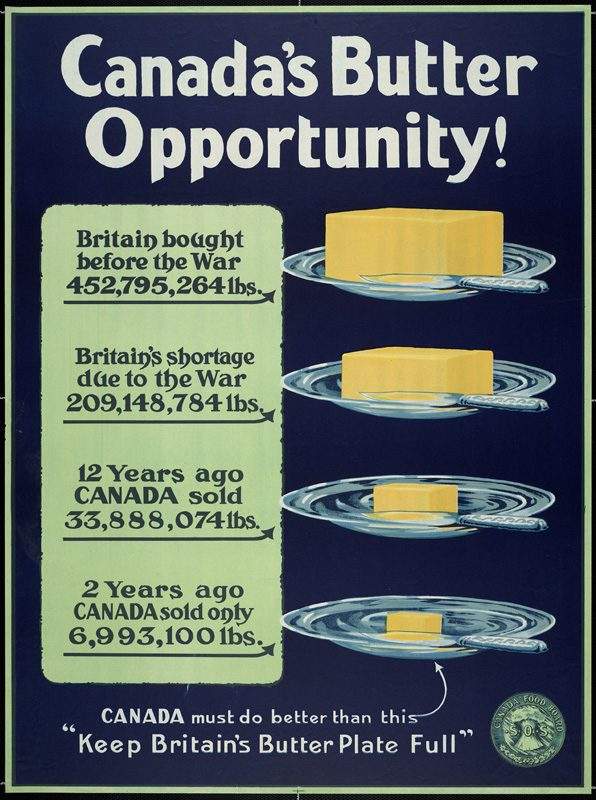

During WWI, the federal government created the Canada Food Board to encourage both agricultural production and frugality in the kitchen. One of its directives was aimed at public eating places: No more than two pounds of sugar could be used per 90 meals served; sugar had to be "yellow" not white; for every four pounds of white flour, at least one pound of alternative flour (oatmeal, corn, whole grain, etc.) had to be used. It also advised: "Do not serve bread and butter before the first course. People eat them without thought." (Some things never change!)

A law was passed making it illegal to stockpile foods such as flour and sugar. The Canada Food Board created a series of posters to drive these messages home like the one pictured above in regards to butter produced in Canada.

Immigrant wives learn how to navigate Canadian tastebuds.

At the end of WWII, the federal government published The Canadian Cook Book for British War Brides so they could satisfy their Canadian husbands. (There were 48,000 European war brides, most of them British.) It included sage advice such as "your man" will prefer pork to mutton; “Suet pudding you would be wise to avoid unless your man has acquired a taste for it overseas;” and "Sausages or bacon are often served with pancakes, but don't forget the syrup even then. The combination does sound odd but when you've tried it you'll agree that it's good."